Strategic Implications of China’s Great Bend Dam on the Brahmaputra River: An Indian Perspective

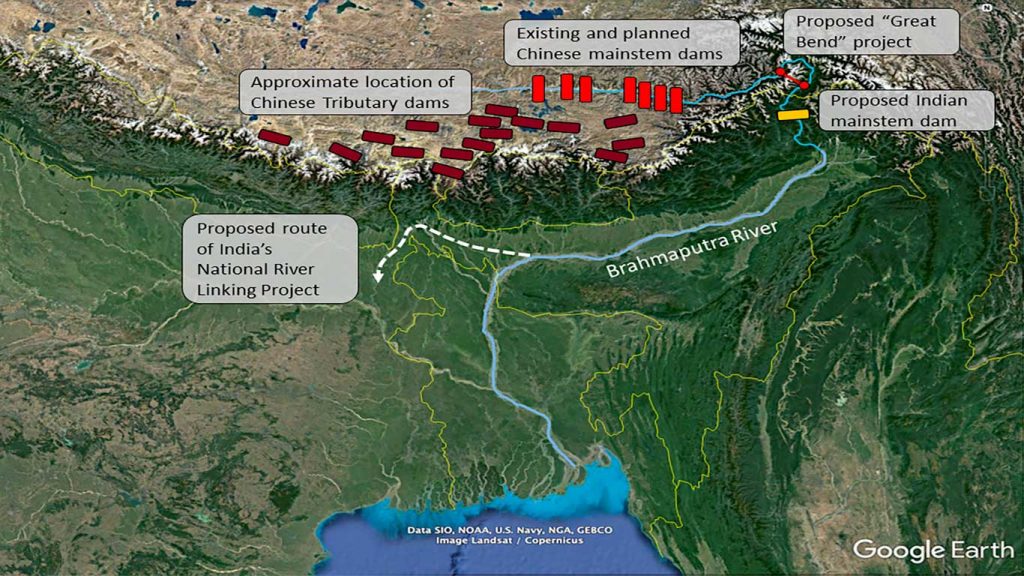

China’s ambitious proposal to construct the Great Bend Dam on the Brahmaputra River is raising significant strategic concerns for India. According to a report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), titled “The Geopolitics of Water: How the Brahmaputra River Could Shape India-China Security Competition,” the dam’s potential to influence water flow into India is immense and multifaceted.

Hydropower Potential and Strategic Concerns

The Brahmaputra River, known as Yarlung Tsangpo in China, reaches its highest hydropower potential at the Great Bend, a point where the river takes a sharp turn and drops 3,000 meters through a gorge before entering India’s Arunachal Pradesh. The proposed Great Bend Dam would harness this significant drop, but its strategic implications are profound.

Political Control and Leverage: The ASPI report suggests that the dam could consolidate Beijing’s political control over its distant borderlands. More critically, it could affect human settlement and economic patterns downstream in India. Furthermore, Beijing could withhold water and data from India, using it as leverage in broader geopolitical negotiations.

Historical Context: India and China signed their first water data-sharing agreement on the Brahmaputra in 2002, which was renewed in subsequent years. However, during the 2017 and 2020 border clashes, Beijing temporarily suspended data sharing, highlighting the strategic use of water as a bargaining tool. The Memorandum of Understanding expired in June 2023, and its renewal is still under diplomatic negotiation.

Ecological and Demographic Effects

From a national security perspective, the dam’s potential to manipulate water flow poses a notable threat. The construction of another massive dam at the Great Bend could exacerbate ecological and demographic effects in lower riparian states, such as India and Bangladesh. The dam could significantly alter the timing of water flows, increasing the risk of floods in India’s northeast.

International Legal Framework: According to the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses, China, as the upper riparian nation, is required to provide prior notice of interventions and consult with downstream states. The ASPI report suggests that international partners could leverage legal arguments to pressure China into greater cooperation and transparency.

Proposed Solutions: The report also recommends forming an open-source, satellite-based data repository, similar to the Mekong Dam Monitor, to provide India and Bangladesh with better data for negotiations and water management.

Water Wars Myth: Hydrology and Geopolitics

Despite the strategic concerns, the notion of “water wars” between India and China over the Brahmaputra may be overstated. Mark Giordano and Anya Wahal from Georgetown University argue that the risk of interstate water conflict is low due to China’s relatively small contribution to the Brahmaputra’s flow. Their analysis, published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, points out that while the Brahmaputra basin spans four states, including China and India, the actual hydrological impact of Chinese water infrastructure on India is limited.

Hydrological Context: The Indian, Bhutanese, and Bangladeshi portions of the basin receive some of the world’s highest rainfall, significantly more than the Tibetan Plateau region controlled by China. Therefore, China’s contribution to the overall flow of the Brahmaputra is lower than commonly perceived. Estimates vary, with figures from the UN FAO suggesting a 30% contribution, while Indian sources estimate as low as 7%.

Climate Change Impact: Climate change is expected to increase overall precipitation in the basin, potentially enhancing water flow despite reduced glacial mass in China’s portion. Consequently, the Brahmaputra’s waters will likely continue to be a source of ecological and geopolitical concern but not necessarily of direct conflict over water resources.

Infrastructure and Geopolitical Influence

The competition between China and India over the Brahmaputra is more about territorial demarcation and control through water infrastructure than actual water scarcity. China’s hydropower projects, including the proposed Great Bend Dam, signify its strategic intent to exert influence over the region.

Territorial Demarcation: India’s plans for its own hydropower projects near the Chinese border underscore the strategic importance of these constructions. Both nations use water infrastructure to assert territorial claims and influence regional geopolitics.

Regional Relations: China leverages India’s perceived intransigence on water issues with its neighbors to build stronger ties with countries like Bangladesh and Nepal. For instance, China has offered to finance Bangladeshi water projects and consistently provides water data to Bangladesh at no cost, unlike its approach to India.

The proposed Great Bend Dam on the Brahmaputra River symbolizes more than just a hydropower project; it represents a strategic tool in the complex geopolitical landscape of South Asia. While the risk of direct water conflict may be low, the dam’s construction and its implications for water management and regional power dynamics highlight the intricate interplay between infrastructure development and international relations. Both India and China must navigate these waters carefully to maintain regional stability and cooperation.

Credits

- Mark Giordano, Professor of Geography, Vice Dean for Undergraduate Affairs, and Cinco Hermanos Chair in Environment and International Affairs, Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

- Anya Wahal, Senior majoring in Science, Technology, & International Affairs, Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

- Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).